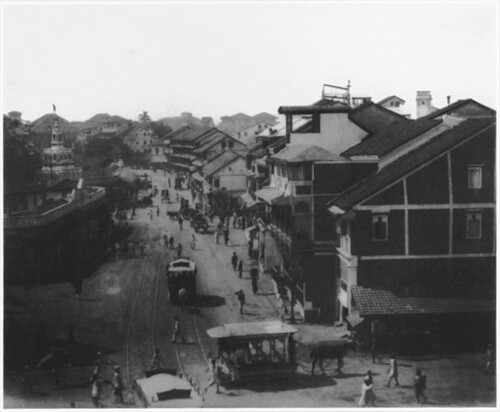

Bombay Municipal Building 1900

Mumbai saw electric lighting for the first time in 1882. The place was the Crawford Market. The following year the Municipality entered into an agreement with the Eastern Electric Light and Power Company. Under the agreement, the Company was to provide electric lighting in the Crawford Market and on some of the roads. But the Company went into liquidation the following year, and the Market reverted to gas lighting. Thus ended the first scheme to provide electric lighting in the city.

Another scheme was taken up for consideration in 1891; and in 1894 the Municipality sanctioned funds for installing a plant to generate electricity. Thecurrent was to be supplied to the Municipal offices and Crawford Market. It was, and the two places were fitted up with electric lights. But by 1906, with the wear and tear of all those years, the machinery at the plant was in a bad way. The current would stop off and on. So, once again, Crawford Market went back to gas lighting. The Municipal offices, however, arranged to get the electricity it needed from the newly established "Bombay Electric Supply & Tramways Company".

This Company was originally established in England, as a subsidiary of the British Electric Traction Company, which had been trying since 1903 to bring electricity to Mumbai. The Brush Electrical Engineering Company was its agent. It applied to the Municipality and the Government of Bombay in 1904 for a license to supply electricity to the city. With the municipality approving the Company’s schedule of rates, the Government issued the necessary license : "The Bombay Electric License, 1905. When the Bombay Electric Supply & Tramways Company came into being, it entered into a contract with the original licensee to take over the right of supplying electricity to the city.

The Bombay Electric Supply & Tramways Company (B.E.S.T.) set up a generating station at Wadi Bunder in November 1905 to provide power for the tramway. The capacity of the station was 4,300 kws. The needs of the city and of the tramway in respect of electric power were bound to grow. At a rough estimate the full capacity of the Wadi Bunder plant was not going to be adequate beyond 1908. The plant could not be expanded much either. So it was decided to set up another generating station, one with a higher capacity, near Mazgaon (Kussara). It started functioning in 1912. The pace at which the demand for electricity grew can be gauged from the fact that within three years the Wadi Bunder Station proved to be inadequate. The tram service had been expanding, and more and more power was needed for the industrial and commercial establishments, as well as for domestic purposes.

Within a year since the B.E.S.T. Company started generating electricity, the Government proposed to issue a license to another concern for the supply of electric power to the city. It was the Tata Company. Its capital and resources were such that the B.E.S.T. Company could hardly stand up against it, as a competitor. The B.E.S.T. Company had cause to worry as to what was going to happen to what it had set up, and its shareholders. Its interests were going to be very badly affected if the Tatas were given a license. It therefore asked for the appointment of a Local Inquiry Committee, under the Electricity Act of 1903, to which it would submit its objections in detail. The Chairman of the Municipality too expressed himself against the proposal to grant a license to the Tatas. There were informal discussions between the representatives of the Tatas and Mr.Remington, Managing Director of the B.E.S.T. Company, with a view to finding out if the differences regarding the proposed license could be settled. A settlement was finally arrived at. Under it, only those whose requirement of electric power was above 5,00,000 units were to be served by the Tatas. This agreement was to be effective for a period of ten years, to begin with. The Tatas were given a license, and they started generating electricity in 1911. The B.E.S.T. Company itself drew on the Tatas when its own production was inadequate. The generating station at Kussara was, of course, functioning. In 1918, owing to insufficient rainfall, there was not enough water in the dam which fed the Tata Plant. The B.E.S.T. Company had to come to the help of the Tatas to maintain their power supply.

Though the B.E.S.T. Company had to take some of the electric power it needed from the Tatas, it was trying to be self sufficient in this respect. But with the outbreak of the First World War, the whole situation changed. The price of coal shot up and the generation of electricity became an unprofitable business. This led the Company to close down its Kussara Station, and it began to get all the power it needed from the Tatas.

The agreement, under which this was done, was made in 1923. It was to be in operation for a period of fifteen years, initially. It could then be extended by a five years’ notice for further ten years. After that an annual renewal of the agreement was provided for. The supply of power under the agreement actually started in January 1925. When the first renewal was due there arose sharp differences of opinion between the Tatas and the B.E.S.T. Company. The most important of these related to those customers who needed more than five lakh units. The Company maintained that the condition in respect of such customers applied only to factories. Whether those whose needs of power increased to more than five lakh units in course of time were customers of the Tatas or the Company was a disputed point. About the same time, the Bombay Port Trust invited tenders for the supply of power. This set off a fierce competition between the Tatas and the Company for the contract. The Tatas quoted a lower rate than they were charging the Company, and the Company quoted almost the same rate. But the rate could have only meant a loss. And the Tatas would have run into legal trouble too, for the Port Trust was not ‘factory’ as required by the old agreement. Moreover, the rate quoted by the Tatas was unfair to the Company. Both the sides now recognised the need for a compromise, and the dispute was settled by leaving to the Company all the customers, except factories, who required more than five lakh units.

Even the Port Trust, which indirectly served as the cause of the compromise had to secure a ‘distributing license’ from the Government to avoid possible legal complications.

1905 to 1911 formed the first stage of the use of electricity in Mumbai. It was not so easily available then. And, of course, the common man could not just afford it. An electric bulb cost two rupees. To have electric lights in your home was status symbol. The luxury was within the means of only the affluent, and most of even those were not mentally prepared to bring this strange thing into their homes.

The second stage was from 1911 to 1920. It made the people of Mumbai fairly familiar with electricity. Electric lighting, everybody agreed, was a good thing, but the importance of electric power to industries was yet to be accepted. The textile mills and other industries still continued to use steam and oil engines for the power they needed. Once electric motors of high power were available, the resistance of these industrialists to recognise electricity as a blessing and a convenience weakened. The Company appointed load canvassers to visit homes and factories for this purpose. The impact of their persuasion was particularly registered by the domestic consumption, which went up considerably. Electrical appliances used in the kitchen and elsewhere drew more and more people to them.

The next phase - 1930 to 1947 - saw tremendous progress in the supply of electricity. A variety of electrical appliances were to be had in plenty. The common man realised what a great help electricity was, and yet, how cheap. The efforts of the B.E.S.T. had achieved their objective. An important development was the setting up of a show-room.

THE SHOWROOM

A show-room was set up in 1926 on the ground floor of Electric House, to give advice to customers on the use of domestic electrical appliances and of electric power, in general. The service was free of charge; but it was aimed at promoting the use of electricity. This service was modelled on similar lines as in England.

A good deal of useful work was achieved by the showroom, apart from instructing people in the use of gadgets. For example, it designed a special kind of electric iron for dhobis, and the tribe of dhobis took to it enthusiastically. Similarly, the showroom fabricated for individual consumers such apparatus as air blowers, sizing tanks and drying cabinets, according to specifications suited to their particular needs. These were not easily available in the market, as the demand for them was limited. With the import restrictions brought by the Second World War, such apparatus were even more sought after, and therefore the service offered by the show-room was even more appreciated.

The Lighting Bureau of the Showroom used to give special advice with regard to the lighting arrangements in offices and factories. The experts on the staff of the showroom would visit the place to see things for themselves before giving their advice. The showroom also started renting out electrical appliances. Refrigerators, which were included in the scheme, became so popular, right from the beginning, that the demand for them could hardly be met. Soon after the inauguration of the showroom. The Times of India of 14th July, 1926 carried a letter about the new service from a reader who signed himself ‘Electric’.

The letter said :

ELECTRIFYING THE HOME

To

The Editor of The Times of India,

Sir,

The Bombay Electric Supply and Tramways Company deserve to be congratulated on their organisation and speedy inauguration of an up-to-date motor bus service for the City of Bombay. Close upon this comes the news of the arrangements that are being made by the same concern to convert, "the poor men’s cottages into prince’s palaces". The report that the company is shortly opening a "showroom" at their Head Office at Colaba for the demonstration of domestic electrical appliances fit for Indian conditions will be received with great joy by all who, though poor, yet possess sufficient "sanitary conscience" to wish to do away once for all with the foul odour of coal and charcoal gas. The millennium does not seem to be far away when one reads that even at "Hackney, one of the most unattractive and depressing parts in London, the local authorities, by assiduous service, have so developed the use of electricity for cooking and heating in these small homes that it is becoming the universal agent, and the supply system contributes between thirty and forty thousand pounds a year to the relief of the rates". But how far the citizens of Bombay will avail themselves of the facilities offered greatly depends upon the efforts the organisers make to spread the "electrical idea" into the home of every family as well as upon the economic efficiency of the "new order of things".

- ELECTRIC

STREET LIGHTING

It was in July 1921 that the Municipality proposed for the first time that the B.E.S.T. Company should undertake to provide street lighting. A scheme was drawn up for installing electric lamps at 47 street junctions. On 1st August 1923 the first lot of 36 lamps was on. They had tungsten filaments. Sodium vapour lamps were tried out on the Horn by Vellard (now called Dr.Annie Besant Road) in 1938.

The Indian Electricity Act of 1903 was repealed in 1910, and the new Act took its place. In 1922 the Indian Electricity Rules came into force. The State secured greater control on electric power. The generation of electricity came to be ranked among the major industries. One of the Rules required every concern producing electricity to supply it to whatsoever applied for it.

WHAT ELECTRICITY COST TO THE CONSUMER

In its application to the Municipality for permission to supply electricity, the Brush Electrical Engineering Company proposed the following tariff :

(1) For lighting : eight annas per unit upto a specific limit (maximum demand). Three annas per unit for consumption in excess of it.

(2) For Power for Industries : eight annas per unit upto a specific limit (maximum demand). An anna and a half per unit for consumption in excess of it.

The tariff was approved. However, the Company’s method of fixing the specific limit was quite complicated. Somehow the pace of growth of consumption fell short of expectations. So an expert was invited to examine the tariff. Following his recommendations the rates were reduced in 1907. For lighting, the basic rate was kept at eight annas, but the subsequent rate was reduced from three annas per unit to two annas; and for industrial power the rate was slashed down to a uniform two annas per unit.

But the Company’s billing procedure continued to be complicated. And the consumers too continued to complain. Finally, in 1908, the Tramways Committee of the Municipality, which had Sri Pherozeshah Mehta as its Chairman, invited Mr.Remington, Managing Director of the B.E.S.T. Company, for a discussion of the matter. Apart from the billing the rate schedule was unfair to those consumers who did not have to keep their lights on late into the night. For them, electric lights cost one and a half times as much as gas lights. The tramway Company therefore wanted the specific limit to go and a uniform rate to be introduced. There were further discussions, and proposals and counter-proposals were bandied, for a good two years till a new tariff emerged. It was as under :

(1) Four and a half annas per unit for lighting, fans and small appliances, per every 250 units consumed in a month, one per cent discount in the bill, 35 per cent being the maximum discount so allowed.

(2) 3 annas per unit for hospitals.

(3) 2 annas per unit for industries.

This schedule was based on the assumption that the payment for the bills would be made at the Head Office of the Company on the Colaba Causeway and that it would be punctual. It was therefore specially stated in the schedule that those consumers who failed to pay their bills promptly would have to pay a deposit.

This schedule was introduced as an experimental measure for two years. It was then confirmed by the Tramways Committee after careful deliberations.

An interesting suggestion was made by the Greaves Cotton Company in 1912. It was regarding the use of electricity to supply heat. If concession rates were offered, the Company pointed out, dhobis would readily use electricity for ironing clothes, and so too would many industrialists. The prospect persuaded the B.E.S.T. Company to lower the rate to one anna per unit for such consumers. This was in 1913.

About the same time Mumbai had its first cinema houses, Four of them - the Alexandra, the Coronation, the Edward and the Gaiety - used to get their electric supply from the B.E.S.T. Company. It first struck the management of the Edward that putting up their own generating plant would mean a cheaper current. It promptly said that it would discontinue the use of its electric power unless a concession in the rate was granted. The Company, realizing what the loss of such customers would mean, promptly reconsidered the matter, and brought down the rate to three annas a unit. Electric illuminations at weddings were coming into vogue; they also were put in a special category for concessional rates. In 1915, the rate for cinema houses was further brought down from three annas to two annas per unit.

Then there was the shortage of electric meters in 1917. It meant that no new connections could be given. Undeterred, the Company announced that it would charge a rupee per point. If your flat had four points, you would have to pay four rupees to the Company every month, no matter how much current you consumed. The rate had been fixed on the basis of the average of all the bills for six months. This exposed the Company to the possibility of a loss, but it preferred some loss of revenue to the loss of consumers, the only alternative in the situation.

Soon the cost of generating electricity started going up, and in 1922 the B.E.S.T. Company approached the Municipality for permission to levy a 15 per cent surcharge on its bills for the supply of electricity. The Tramways Committee of the Municipality refused to oblige. In 1930, the Municipality asked the B.E.S.T. Company to lower its rates on the ground that an essential item like electricity should be available to the people at a cheap rate. The Calcutta Electricity Company was cited as an example in this respect.

The Company’s stand in this respect was explained by its General Manager in his letter to the Municipality in 1930. The points he made were : (1) The rates in force had been fixed in 1910, and there had been no increase in them since. In Bombay, electricity was the one item of which the price had not gone up for years together. (2) The Company got its electricity from the Tatas at so much per unit and it supplied it to its consumers as so much per unit. It was naively thought that the difference between the two rates was the Company’s profit per unit. It was not all that simple. The voltage of the power received from the Tatas had to be reduced, and this operation cost the Company quite a bit. Then there was the leakage on the lines carrying the current to the consumers. Such wastage ordinarily amounts to 15 per cent. That is, for every 100 units drawn from the Tatas, only 85 actually reached the consumers.

There was yet another point. What profit the company made on the supply of electricity helped it run its tramway service, which charged a flat rate of one anna, the lowest for any transport service in the world, as had been pointed out by Mr.Dalrymple. The bus service too was a liability, but it was being run to supply a real civic need. The attention of the Municipality was drawn to this fact.

Meanwhile, an expert was invited from England to examine the Company’s schedule of rates. He arrived in Mumbai in December 1929. His conclusion was that the rates were generally fair. Some modifications were made in the schedule on the lines suggested by him. Those were the days of a trade depression, and the Company showed its awareness of it by cutting down its rates wherever it could.

The State Government appointed a committee in 1938 to study the Company’s tariff and advise the Government on what the maximum rates should be for the various categories of consumers. The Government accepted the committee’s recommendations and asked the Company to give effect to them from 1st April, 1939. The revised rate were : 2 annas per unit for lighting and fans, three quarters of an anna per unit for electrical appliances; and four annas per month as the meter rent. There was a similar reduction in the rates for the other categories.

However, the Government gave an undertaking to the Company that it would not ask for further reduction for five years, and that the Company would be exempted from the Sales Tax during this period.

Any organisation supplying electricity tries to encourage its use by offering attractive rates. So did the B.E.S.T. Company. But it had to abide by its agreement with the Municipality which stipulated that such reduction in rates should apply to all the types of consumers.

The Company’s agreement with the Tatas regarding the supply of electric power was renewed in 1938. Now the power cost less to the Company, which in its turn passed the advantage to the consumers. For example, till 1934 the rate for lights was four annas per unit. By 1938 it had come down to 3 annas upto 14 units, and two and a half annas thereafter. There was a similar lowering of the rates for the other types of consumption.

Electricity was generated for the first time in Mumbai in 1905. During the next forty years its consumption went up from 1,50,000 kilowatts to 60,00,000 kilowatts. Used for a variety of purposes, both domestic and industrial - and that at a low rate - electric power assumed an important place in the life of the people. This underlined the necessity for some kind of a state control on its use, in the interest of the consumer, as well as of the producer.

TAX ON ELECTRICITY

The Government imposed a tax on electricity for the first time in 1932. The tax was imposed to help the State tide over the financial difficulties created by the trade depression, as the official explanation went. However, like several other taxes, the tax on electricity settled down to become a regular feature. The Municipality, as well as many other public bodies, protested strongly against the new imposition, but it was of no avail. With the tax added, electricity bills went up by more than fifty per cent and, as an inevitable result of it, the growth in the consumption of electricity slowed down. In 1936, and again in 1940, representations were made to the Government for repeal of the tax. Actually, the half annas impost of 1932 moved upto three quarters of an anna in 1938, and to an anna and a quarter in 1939! The latter jump was designed to cover the expenditure on prohibition.

This is the story of the early days of electricity in Mumbai - of its arrival and the expansion of its use. In modern life electricity is next only to air, water, food and shelter as a necessity. Electricity is certainly a blessing, but it can very nearly be a curse if man depends too heavily on it. All that he can do is to take every precaution against the blessing turning into a curse.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

IndiaTICCA GADIS. These horse-drawn Victorian carriages that were the only mode of transport to come to Bombay in 1882 after The Bombay Tramway Company Limited was formally set up in 1873. Motor taxis were introduced in 1911 whereas motor buses started plying in 1926. Today, the Victorias in front of the Taj have been replaced by black and yellow taxis. But, one can still hire a Ticca Gadi for a negotiated sum and drive along the sea face for an experience.

IndiaTICCA GADIS. These horse-drawn Victorian carriages that were the only mode of transport to come to Bombay in 1882 after The Bombay Tramway Company Limited was formally set up in 1873. Motor taxis were introduced in 1911 whereas motor buses started plying in 1926. Today, the Victorias in front of the Taj have been replaced by black and yellow taxis. But, one can still hire a Ticca Gadi for a negotiated sum and drive along the sea face for an experience.

IndiaTICCA GADIS. These horse-drawn Victorian carriages that were the only mode of transport to come to Bombay in 1882 after The Bombay Tramway Company Limited was formally set up in 1873. Motor taxis were introduced in 1911 whereas motor buses started plying in 1926. Today, the Victorias in front of the Taj have been replaced by black and yellow taxis. But, one can still hire a Ticca Gadi for a negotiated sum and drive along the sea face for an experience.

IndiaTICCA GADIS. These horse-drawn Victorian carriages that were the only mode of transport to come to Bombay in 1882 after The Bombay Tramway Company Limited was formally set up in 1873. Motor taxis were introduced in 1911 whereas motor buses started plying in 1926. Today, the Victorias in front of the Taj have been replaced by black and yellow taxis. But, one can still hire a Ticca Gadi for a negotiated sum and drive along the sea face for an experience.

![[Tram+in+Delhi.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj9ERFDwc3u1WcPSBl-FKQavjACVFh4ntdvWXvUTTHxBrMHXDVrbn_kOzHqAOOV78pvnsKPn_MbAdq9N43owPwx1FKa2ezuJ1_sXhh3FV1-LloBDxv7u0nQxirpEFjz_hNpkm-9pq5QbmwW/s1600/Tram+in+Delhi.jpg)

No comments: